There are many public transit “maybes” in St. Louis right now. Its been eight years since the eight mile MetroLink Blue Line opened in 2006, but its not clear where the next substantial transit expansion will be built. Political leadership hasn’t established a top priority among a handful of proposals. Population density drives transit ridership as much as any other factor, but will the next expansion serve the most densely populated part of St. Louis? And Metro, stuck with long-term debt from the last MetroLink expansion and perpetually starved for state funding, operates in an extremely constrained capital expenditure environment.

While state funding is MIA, what isn’t in question is demand for transit. Metro’s routes that connect dense residential areas with employment or educational centers have high ridership. While Metro has acknowledged that a major network expansion is off the table without an additional revenue stream, independent groups are pushing their own transit initiatives. Even MoDOT’s surveys show St. Louis area residents want transit expansion more than they want additional road capacity.

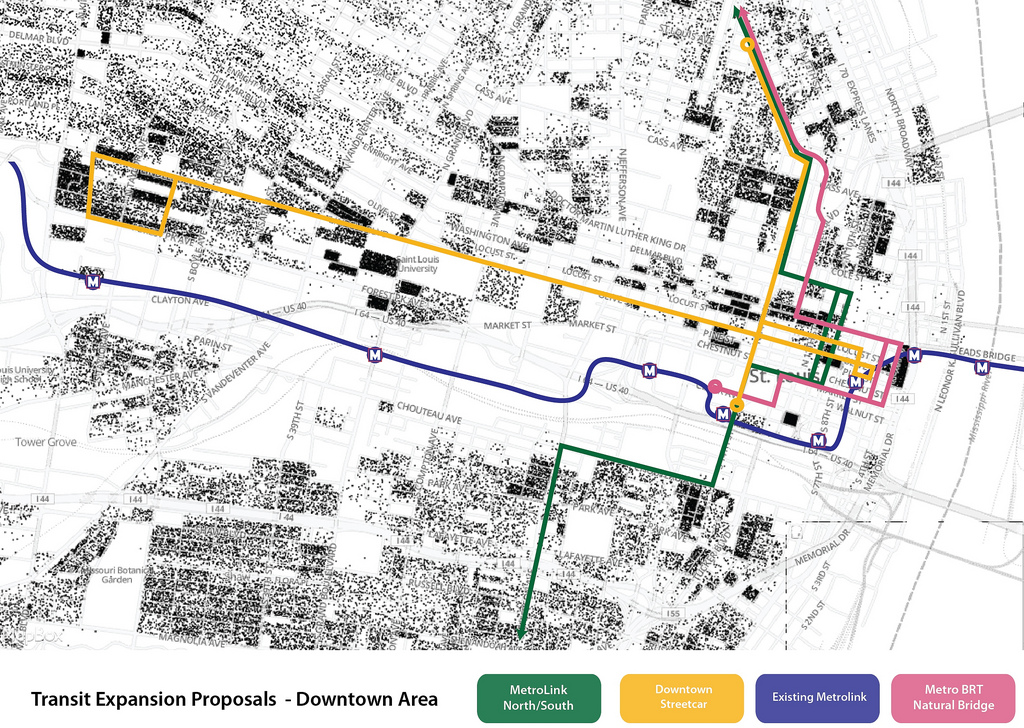

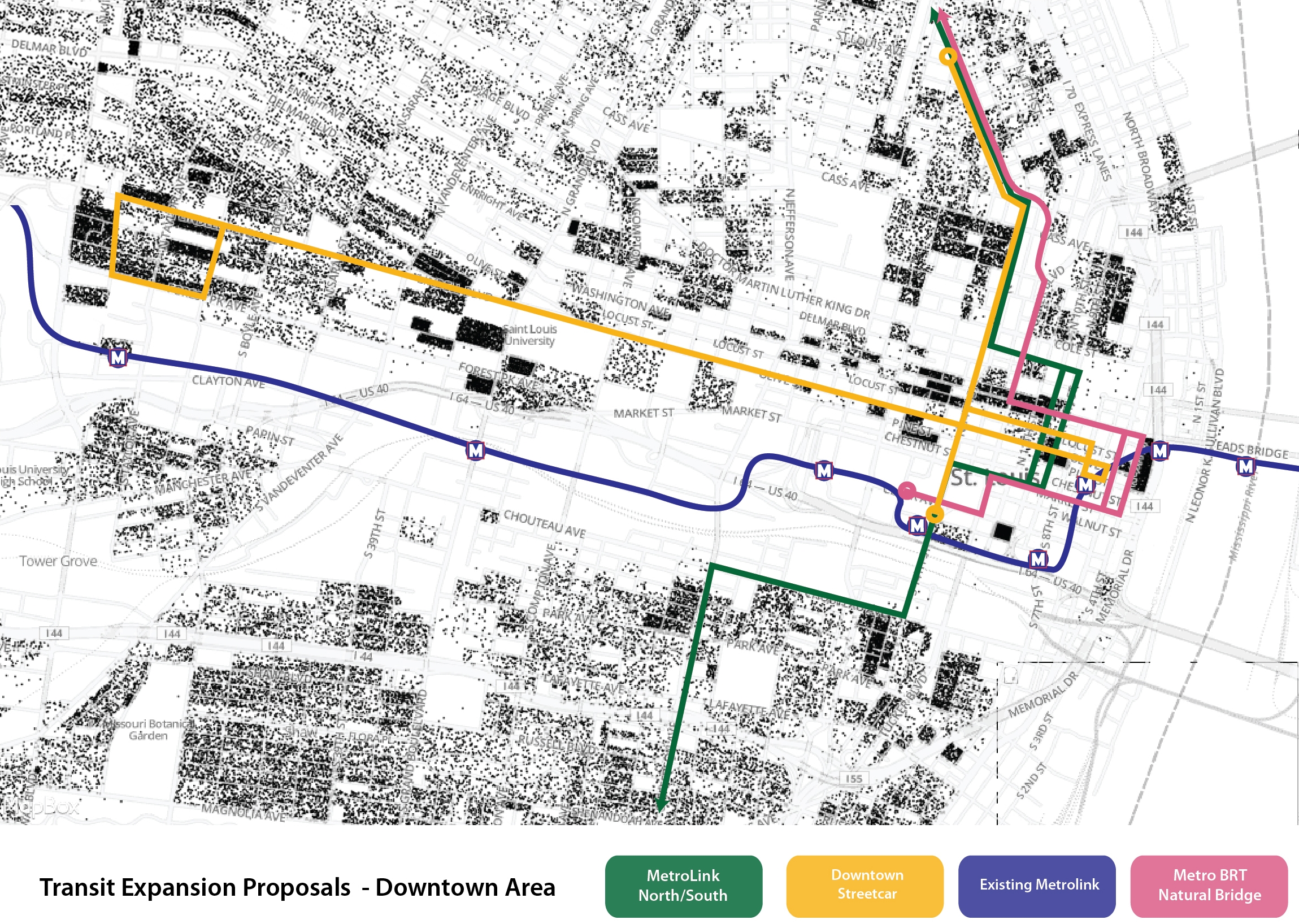

Years of regional leadership equivocating on transit priorities have left us with a long list of possibilities: the North/South MetroLink alignment, the Downtown Streetcar, Bus Rapid Transit, and the Loop Trolley. But which of theses projects most enhances the existing network? No one at the top of the political/transit heap has expressed a strong preference for any of them.

What does transit look like when its not driven by the region’s transit agency? The default test case for transit expansion absent a clear regional strategy is the Loop Trolley. The 2.2 mile on-street project scored an FTA Urban Circulator grant of $25 million in 2010. Other funding for the $44 million project is derived from institutional contributions and a sales tax overlay along the route.

Delays with the project since the federal grant announcement lay bare the limitations of this arrangement. Building and running a streetcar line, even just 2.2 miles of track, is no easy task. While Metro isn’t a flashy agency, it does possess the engineering and financial expertise to plan and execute a project. The Loop Trolley Company, while a great expression of transit-desire bootstrapping, simply doesn’t have the same expertise available. By mid 2013, in danger of losing their federal funding for not showing sufficient progress, Metro stepped in and loaned their chief engineer Chris Poehler to the effort. They’ve since been able to meet deadlines set by the FTA, but it remains to be seen whether the Loop Trolley can stay on sound fiscal footing without being tethered to the guaranteed revenue stream of a larger transit agency. The groundbreaking date for the project still isn’t firm. Meanwhile Cincinnati’s streetcar, awarded the same federal grant in 2010, broke ground in early 2012 and despite political fireworks around its construction, remains projected to open in 2016.

Going forward, it should be clear Metro needs to be the lead agency on transit projects. The political liability of another false start is too high. St. Louis already has a fractured political landscape, the region can’t handle a jigsaw puzzle of transit agencies.

The original MetroLink line was built primarily in available railroad right of way. All the new proposals are street running. While street running systems tend to be more expensive and complicated to build, they also have the distinct advantage of more route options and highly visible, accessible stations. A street running system goes where people already are, it’s built directly into the existing urban fabric. In St. Louis, that means an urban fabric that grew up around the pre-1950’s streetcar system. The dense, fine grained residential and commercial environment in south St. Louis was built to allow people to walk to their streetcar (we should remind ourselves they were practically everywhere) and will function in largely the same way when that infrastructure returns.

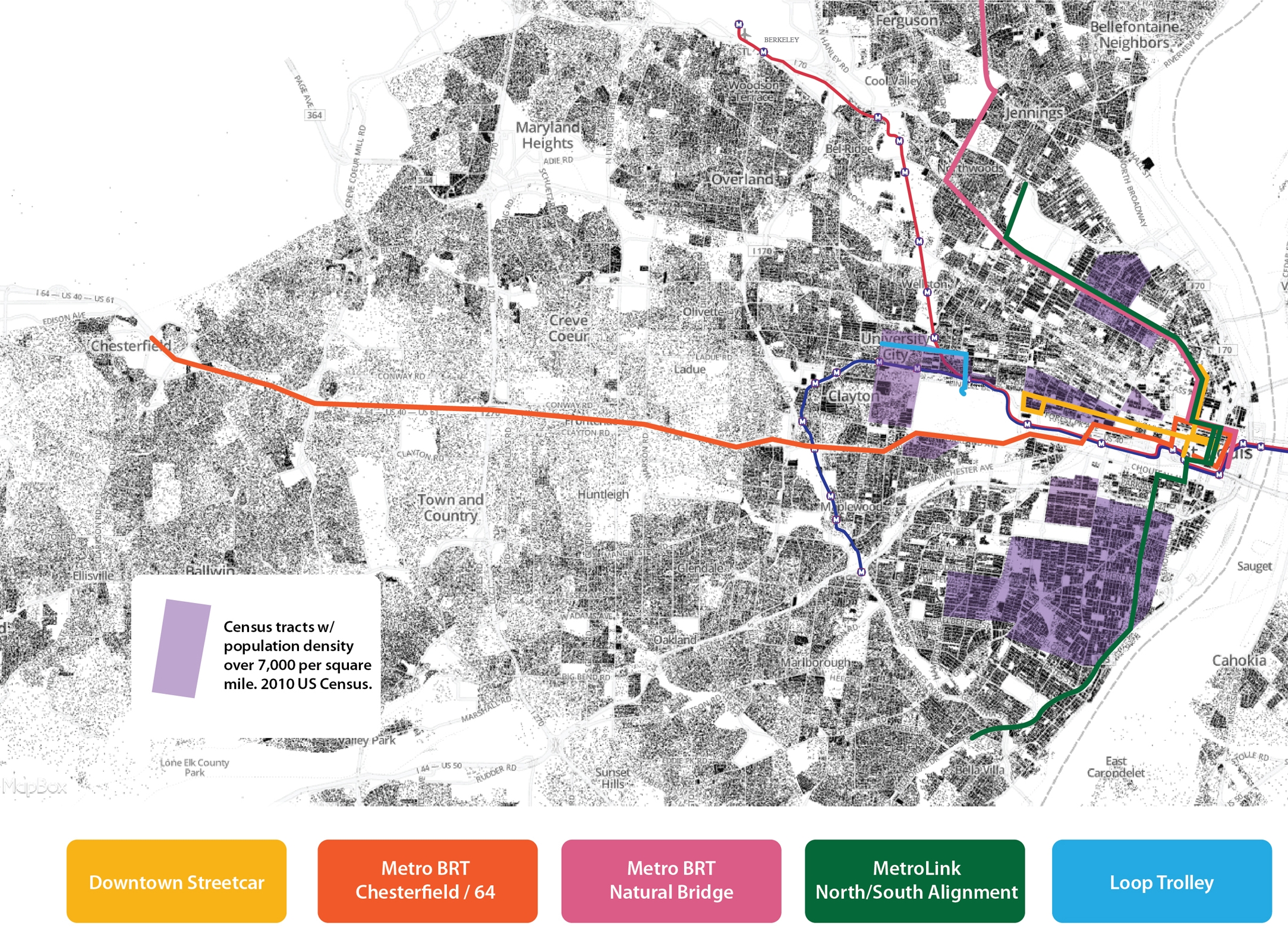

A large part of south St. Louis, from I-44 on the north to Carondelet Park on the south, and Broadway on the east to past Kingshighway on the west, contains block after block of intact multifamily flats and densely packed single family homes. This large area suffered almost none of the neighborhood clearance of the central corridor in the 1950s and 60s and very little of the vacancy that affects north St. Louis. Population density ranges from 7,000 to 13,000 people per square mile. Outside of a few blocks of the Central West End, this is the highest in the region.

The three major proposals on the drawing board consist of 5+ transit lines. What should alarm both transit advocates and riders is only one of five proposals serves the densely populated, built-for-transit southside. And sadly, its the proposal that no one, not even Metro, is talking about. Metro has barely uttered the words, “MetroLink South” since they finalized the preferred route in 2008.

Why is no one talking about MetroLink South? Without an investment by the state of Missouri, there’s no chance to pay for it in the near future. But there can be little argument this area is the best suited to deliver high ridership on a new line. While the region has an abundance of east and west transportation options, fewer run north and south. South St. Louis has the demographic mix most likely to want and use transit. Bus Rapid Transit between downtown and the Chesterfield Mall will be built before downtown is connected to the population dense, car optional southside.

North of downtown, the MetroLink North route and the Natural Bridge BRT line would follow essentially the same alignment. The lower capital cost of BRT and lighter touch infrastructure means Metro can move some of the same people MetroLink North would serve, for a fraction of the upfront cost. The region has no funding plan for MetroLink South, and is actively pursuing a bus line that replicates MetroLink North. Metro should pull back the curtain and admit that building the North/South Metrolink alignment is already off the table for most of our lifetimes.

A glance at the Metro system map shows they provide bus service to almost the entire 584 square miles of St. Louis City and County. Because St. Louis County, with its larger population and sales tax base, actually pays the bulk of the tab for Metro, their mandate is to cover as much of the County as possible. Where most other transit agencies can prioritize service on the busiest routes, Metro’s busiest buses (the 70/Grand) leaves riders on the sidewalk while routes like the 210/Fenton Gravois Bluffs serve few passengers. This shotgun approach to resource allocation means Metro also generates less fare revenue from each route than they could.

What’s the funding solution that allows Metro to make decisions based on where the most riders are? Is it an additional sales tax like the Loop Trolley is using, or property tax surcharges like the Downtown Streetcar has proposed? I’d argue its neither. Even a modest funding stream from the state of Missouri, on the order of $20 to $30 million a year, would allow Metro to prioritize service improvements to routes with the most ridership. $20 million a year represents only .2% of the state’s discretionary budget, while it would account for around 8% of Metro’s annual budget.

The region’s fractured, dysfunctional political infrastructure is again failing its physical infrastructure. There’s no funding strategy to get light-rail to the location that would most benefit from it, while regional leadership is leaving the transit discussion to second tier players. Business and industrial leadership aren’t using their leverage at the state level to secure a modest, reliable stream of funding from the state. Metro’s current funding mechanism is pushing them to chase new sprawl in Chesterfield over built-for-transit south St. Louis. While the abundance of transit possibilities create a veneer of progress, the region is quietly in a public transit state of crisis.