St. Louis is full of intersections that are difficult for pedestrians and bicyclists to navigate. This is the outcome of a century-long history of projects that made the city’s streets more generous for cars. Starting in the 1920s, St. Louis embarked on a long, expensive campaign to create a system of broad arterial roads that could ferry large volumes of traffic across the city. From that point on, pedestrian comfort was no longer the priority, and the popularity of bicycling as a mode of transport quickly faded from the high it reached in the 19th century.

Strong Towns – Youtube – The Stroad

The city’s big arterial roads—Grand, Jefferson, Market, Chouteau, Lindell, Page, etc.—are household names, the main thoroughfares connecting the city’s densest places. However, their poor design has fragmented the city into islands of walkability. These “car sewers,” characterized by high volumes and speeds, are perilous places for pedestrians and bicyclists. Along the eastern border of Forest Park Southeast (FPSE), Chouteau Avenue (Missouri Route 100) and Vandeventer Avenue are textbook examples of excessively wide roads that suffocate pedestrian and bicyclist mobility. The walkable, bikeable neighborhood to the west is eroded by a congested corridor dominated by auto-oriented land uses.

Nextstl – MoDOT, Gross Negligence and Death on St. Louis Roads

I recently had the unpleasant experience of trying to navigate the intersection of these two roads on a bike. It was easily the dodgiest part of my ride that day. Heading east from FPSE, I was unsure of how to ride through the intersection to the bike lanes on Chouteau. On my way back, I nervously navigated the opening of the right-turn lane from Chouteau to Vandeventer. After crossing the intersection, I found myself dumped into a car lane, forced to merge with oncoming traffic.

These deficiencies suggest the main issue is a lack of delineation, one of the most important components of safe intersection design for pedestrians and bicyclists. Where are different users of the road supposed to go? Is there an obvious path for each user to get from one leg of the intersection to another?

Nextstl – Bike Box Coming to Tower Grove and Vandeventer

MoDOT has completed various projects around this intersection over the past couple of decades. To the east, the Chouteau bridge over the railroads was reconstructed in 2005. Bike lanes were added to Chouteau from Vandeventer to Broadway in 2016. To the west, Manchester through The Grove was “dieted” from four to two lanes in 2010; this project also added sharrows and crosswalks. These modifications represent a concerted effort to make MO-100 a primary bike route across the city, and the Strava heatmap suggests it’s been successful at attracting riders. However, at this particular intersection, designers sacrificed bicyclist comfort to improve car throughput. Heading east, Chouteau widens from two to four lanes at the intersection, leaving little room for bicyclists.

USDOT Federal Highway Administration z Youtube – Road Diet

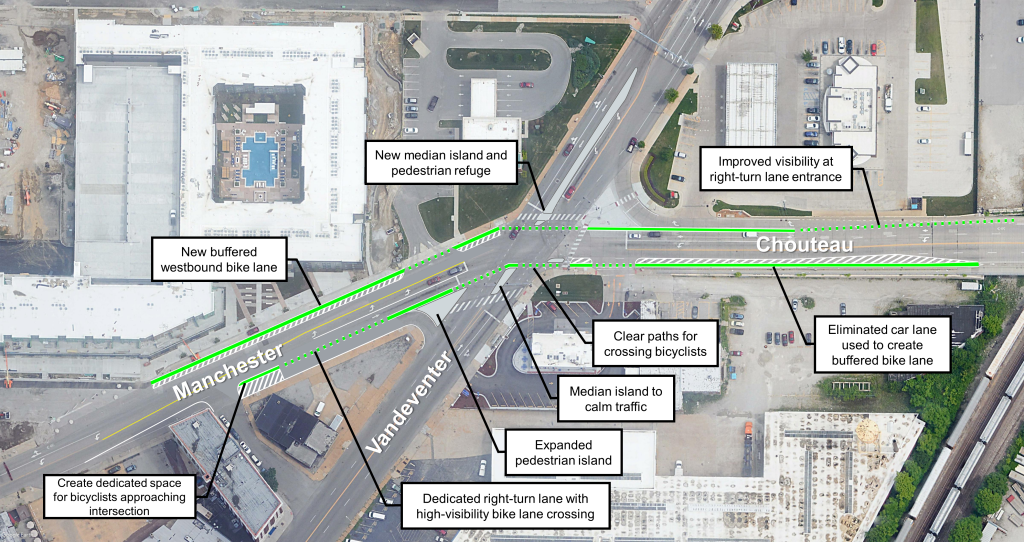

By pushing this widening from west of the intersection to east, we can solve many of the problems I encountered. This change is as simple as removing just one of the eastbound through lanes on Chouteau. My conceptual design, shown below, pushes the widening of Chouteau 500 feet east of the intersection. For eastbound bicyclists, this design uses the reclaimed car lane to create a buffered bike lane that would safely carry them through the intersection.

For westbound bicyclists, the changes are even simpler. Adding high-visibility green paint to the opening of the westbound right-turn lane would help bicyclists and drivers navigate the crossing. On the other side of the intersection, narrowing the existing car travel lane (currently an excessive 15 feet wide) and removing a small concrete median creates a new bike lane. The new design provides an easily-identifiable path for bicyclists to travel through the intersection, with dedicated space for them on both sides.

This design also creates new space for pedestrians. The pedestrian island at the southwest corner of the intersection would be expanded significantly. On the north leg, eliminating one of the two southbound left-turn lanes creates a new median refuge island for pedestrians. The eliminated turn lane also creates space for a refuge island on the south leg of the intersection, again buffering the crosswalk. Median islands improve pedestrian safety and reduce speeding.

Closing a travel lane will impact the vehicular capacity of the intersection, but when weighed against the safety benefits for pedestrians and bicyclists, the cost is minimal. The two-lane road diet on Manchester in The Grove already constrains the corridor’s vehicular capacity, so pushing the start of the four-lane section east of the intersection will likely have a negligible impact on the overall throughput of MO-100. The Grove is a hotspot for bicyclist and pedestrian activity, this intersection should accommodate it. Furthermore, improving conditions for bicyclists at this difficult intersection would enhance the overall usability of the Chouteau bike corridor. Ultimately, this could remove cars from MO-100 in the long run by making bicycle trips more attractive and viable.

Best of all, these changes don’t require reconstructing the road. MoDOT can use paint and cheap separator devices, like the zebra. The expanded pedestrian and median islands can be added using concrete overlays—the new raised surface would be installed on top of the existing roadway, no subsurface work required. Alternatively, the new pedestrian space could be created using paint and bollards as has been done in many other cities.

Jurisdictional issues have prevented the implementation of protected bicycle infrastructure on the city’s major arterials. MO-100 is under the purview of MoDOT, which has adopted more conservative design standards for bicycle infrastructure than the City. The agency’s recent redesign of Gravois (MO-30), featuring unprotected bike lanes, is a good example of its design philosophy. MoDOT intends for state routes like MO-100 to carry significant volumes, including truck traffic. It designs to this end, which explains the generous lane widths and intersection layouts. In the hierarchy of roads, state highways are just below the freeway system.

Going forward, it’s worth questioning whether these state route classifications are still appropriate in urban areas. With I-64 and I-44 providing high-speed, limited-access east-west travel a short distance to the north and south, respectively, do Chouteau, Manchester, and Vandeventer still need to prioritize vehicular capacity and speed? As neighborhoods like FPSE densify, shouldn’t their main thoroughfares adapt to the new context?

The changes proposed here would dramatically improve conditions for pedestrians and bicyclists, contributing to the city’s Vision Zero and sustainable transportation goals. Additionally, they would help us reimagine the distribution of road space in dense urban neighborhoods. If there is one benefit of St. Louis’s oversized streets, it’s that there are plenty of opportunities to cheaply and quickly create new space for pedestrians and bicyclists with minimal impacts on traffic. This concept for Chouteau at Vandeventer is just one example of the many ways we can use thoughtful design to make St. Louis’s streets healthier, safer, more attractive, and more equitable for all users.

Note: The conceptual design shown here was not created by a licensed Professional Engineer and is not an engineering drawing. Implementation of the ideas described here would require formal study and design by a licensed engineering firm.