Thanks to Board of Alderman Financial Analyst Gerard Hollins for working with the St. Louis Assessor’s Office and Planning Department to help categorize the data included in this article and map.

St. Louis faces a growing paradox few other cities face to the same degree: growth in land ownership of non-profits, hospitals, universities, and government owned parcels is depleting an already constrained tax base. While post-industrial cities have benefited from the growth of the “Eds and Meds” economy, the physical growth of these institutions has removed significant land from the property tax rolls.

The situation is particularly challenging in St. Louis due to a confluence of factors, some obvious, some unique to Missouri and St. Louis. State government exempts non-profits from paying property taxes, which is common. State law also exempts non-profits from paying sales and use taxes, which is unusual nationally. Local law exempts non-profits from the St. Louis payroll tax, a .5% tax on payroll paid by for profit companies. As a result, even if universities and hospitals are thriving, both the St. Louis Public School District, and a variety of programs funded by sales and use taxes in St. Louis do not see additional revenue. With the exception of the payroll tax, these tax exemptions are determined at the state level, out of the hands of local lawmakers.

St. Louis faces the added challenge of six decades of population decline, leaving in its wake a large surplus of government owned parcels. Extensive federal highway infrastructure, a large parks system, and several large cemeteries within city limits have further permanently reduced the amount of taxable land within St. Louis.

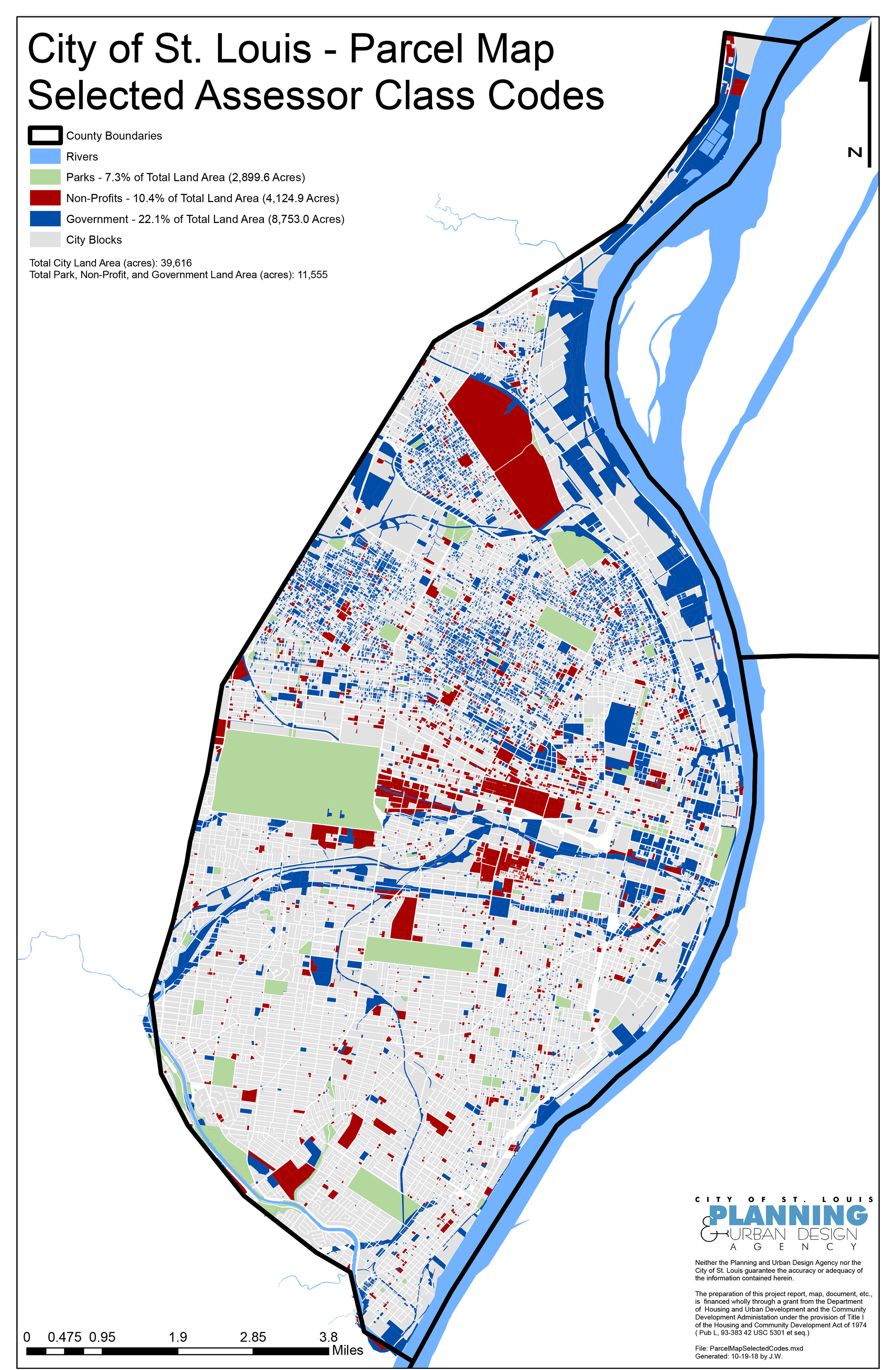

While there has been speculation on the topic, prior to this article the extent of this problem had yet be mapped. Today fully 40% of St. Louis’ 62 square miles are exempt from property tax. Only the remaining 37.2 square miles in the City generate property tax revenue. The City of St. Louis has one of the smallest total areas of taxable property of any major city in the United States. There are a few comparable cities. Places like San Francisco, Seattle, Minneapolis, Boston, Miami, Baltimore, and Buffalo, New York all share a small geographic footprint. But all of these places, except Baltimore, have either exceptionally high property values or are part of a larger surrounding county, or both.

St. Louis stands almost alone nationally as a low real-estate value central city with scarce land available to tax, separated from the surrounding county.

The non-profit sector of the economy has been making steady gains for decades, in particular colleges, universities, and hospitals, as more Americans enrolled in post-secondary education and health care grew its share of the national economy. The non-profit sector now accounts for 10% of the entire U.S. workforce. The percentage is often higher in urban areas with a high concentration of hospitals and universities, such as St. Louis. The tax environment in Missouri is more accommodating of non-profits than average. Missouri exempts non-profits from charging sales tax on the their own sales (think the cafeteria in a hospital). They also exempt non-profits from paying sales and use taxes on their purchases. When BJC buys 100 computers, or St. Louis University buys building materials, they pay no sales tax on the purchase. It is unknown exactly what revenue is lost to cities and the state of Missouri because of this exemption, because there is no reporting requirement for these purchases.

In St. Louis a rough estimate is 10% of the total sales and use tax receipts are tax exempt. Assuming non-profits make purchases at roughly the same rate overall as for profits, this would amount to $14 million in lost sales and use tax revenue each year.

If we further assume that 10% (this is a very conservative estimate) of the total local payroll is paid to employees of non-profits, then the city foregoes an additional $3.9 million in annual payroll tax revenue.

Finally, non-profits make up slightly more than 10% of the city’s land area. The large non-profits (hospitals, universities) occupy real estate that is much more valuable than average. A safe assumption is that the City forgoes about 15% of its share of property tax revenue to this exemption, or about $9.2 million annually.

In total, a conservative estimate of non-profit tax exemptions amount to about $26 million a year in revenue the City of St. Louis is unable to collect.

As the school district is the primary recipient of property tax revenue, it fares worse. SLPS will miss out on about $31.7 million in revenue this year because of non-profit property tax exemptions, or roughly 10% of their entire budget. Perhaps another $1 million in SLPS revenue is forgone because of the sales tax exemption.

Combined the City and SLPS (the two major local taxing jurisdictions) miss roughly $59 million annually across the four tax exemptions, (property, sales, use tax, and payroll) a not insignificant number. (These estimates are derived from revenue figures in the city’s annual budget.)

Like many issues within the St. Louis region, the problem is exacerbated by the fragmentation of the City and County. Major institutions, non-profits, and property owned by various governmental entities are concentrated within the City of St. Louis. The city contains a disproportionate share of the region’s tax free amenities and institutions. The proportion would drop substantially if the 500+ square miles of St. Louis County were combined with the city as one taxing jurisdiction.

There is no easy fix. State law and the state constitution establish the property tax exemption for universities and hospitals. There is zero probability of that changing. State law also creates the sales and use tax exemptions. While an unusual policy, it’s difficult to see the political will to remove those exemptions, given the economic importance and political clout of hospitals and universities in the state. Only the payroll tax is within the power of local lawmakers to levy – a subject that has arisen in the recent past but was met with substantial opposition from major local institutions.

The big two: Washington University / BJC and Saint Louis University / SSM do make what amount to voluntary PILOTS (Payments In Lieu of Taxes) on property they own which is vacant and not used in connection with the mission of either organization.

The irony of the growth of the non-profit higher education market is that locally it reduces revenue available for primary education. As more land comes off the tax rolls, less is available to generate property tax revenue to the school district. The interests of primary public education and private secondary education are clearly at not aligned.

What is fair, and what is possible may be two very different things. While some cities (Boston) have been successful at negotiating payments from non-profits that amount to a percentage of what they would owe on a market basis, those payments are generally still voluntary and a degree of uncertainty surrounds them.

Of course these institutions still use city services, sometimes fairly intensively. Their employees do generate local tax revenue via the 1% earnings tax. Their concentrations of employees and visitors also help create a market and sustain other local businesses. The issue is not black and white, but as more property becomes tax free, either via non-profit expansion, local government having to take ownership of tax delinquent properties, or other federal or local government institutions expanding (NGA, Zoo, etc.) the dynamic becomes more problematic for a city with an already stagnant tax base.

While a solution like negotiating tax-like payments with universities and hospitals may be elusive in the short term, at a minimum St. Louis and the St. Louis School District should conduct a more through investigation to understand exactly how much revenue is being lost to these exemptions. Addressing the issue with more compelling data, rather than speculation, will help local government engage the non-profit sector in a more productive way on their shared responsibility to the communities they exist in.