It’s autumn in St. Louis — so while the pumpkin spice crowd lines up for lattes, we’re raising steins instead. So dust off the lederhosen and dirndls, tip your Alpine hat, and loosen up those polka knees. Oktoberfest isn’t just another seasonal party here; it’s a hometown tradition with deep roots.

St. Louis owes much of its flavor to German immigrants who helped build the city — from brickworks and railroads to beer halls and breweries. Their lager know-how, neighborhood beer gardens, and communal spirit shaped how we celebrate today. That’s why Oktoberfests pop up across the region, from cozy block gatherings to mega-tents, with local breweries pouring German-style festbiers that tip the cap to the people who made St. Louis a beer city. Prost!

From royal toast to worldwide fest

Oktoberfest began in Germany: Munich’s 1810 wedding party for Crown Prince Ludwig and Princess Therese grew into the world’s largest Volksfest. It runs from mid-September to the first Sunday in October, and when October 3 (German Unity Day) falls after that Sunday, it continues until the holiday. Roughly seven million visitors enjoy rides, food stalls, and traditional Bavarian dishes — along with about 7.4 million liters of beer.

Why Germans chose St. Louis

St. Louis built a reputation as a destination for European arrivals. By the mid-19th century, we had welcomed a variety of immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Germany, and other locales. Many of these new residents were fleeing political and economic troubles in their homelands and seeking new opportunities for themselves and their families.

St. Louis became a German destination after writer Gottfried Duden praised our region in his 1829 account of his travels here, Report on a Journey to the Western States of North America. He dubbed the Missouri River valley “America’s Rhineland” because climate and topography felt familiar.

Soon, many Germans took him at his word and headed to Missouri. With steamboat travel, St. Louis was more easily accessible than many other locations in the new United States. Just as important, the region was known for welcoming people of varied religions and socioeconomic backgrounds. A growing Catholic population improved the odds of acceptance for German Catholics, and that welcome extended to Lutherans, Jewish communities, and nonconformist sects.

By 1850, well over half of all St. Louisans were born in either Ireland or Germany. German communities blossomed across the map, including Soulard, Benton Park, Benton Park West, Marine Villa, Dutchtown, Compton Heights, and Gravois Park on the South Side; Baden, Old North St. Louis, Carr Square, and Bremen (now Hyde Park) on the North Side. You can still hear the echo of Germany in names like Baden and Bremen.

In short, newcomers didn’t just arrive; they settled in, stitched neighborhoods together, and made the city feel a little more like home.

The city that the Germans helped to build

Many German immigrants arrived with education and trade skills, and they quickly put these skills to work. They helped build the city from the ground up — working in clay pits and brick companies, in steel mills, smelting facilities, coal mines, and the railroads — while also driving sectors like meatpacking, manufacturing, hardware, warehousing, flour milling/refining, and (of course) beer brewing. If it moved, milled, stacked, or poured, chances are Germans had a hand in it.

They also brought a love for lager and put our cave system to work, enabling steady production long before mechanical refrigeration. Without German immigrants, there’d be no Anheuser-Busch or most of the other breweries dating back to before the Civil War. The beer story isn’t a footnote — it’s part of the blueprint.

Henry Overstolz, German immigrant and 24th Mayor of St. Louis, 1876-1881. Missouri Historical Society collections

Their civic footprint mattered just as much. Germans arriving in the late 1840s and early 1850s were often ardent abolitionists whose activism helped keep Missouri in the Union during the Civil War, making St. Louis a Union stronghold and home to a critical federal arsenal.

By the dawn of the 20th century, German St. Louisans weren’t just newcomers — they were the fabric of the place, running businesses, shaping culture, and even sitting in the mayor’s chair.

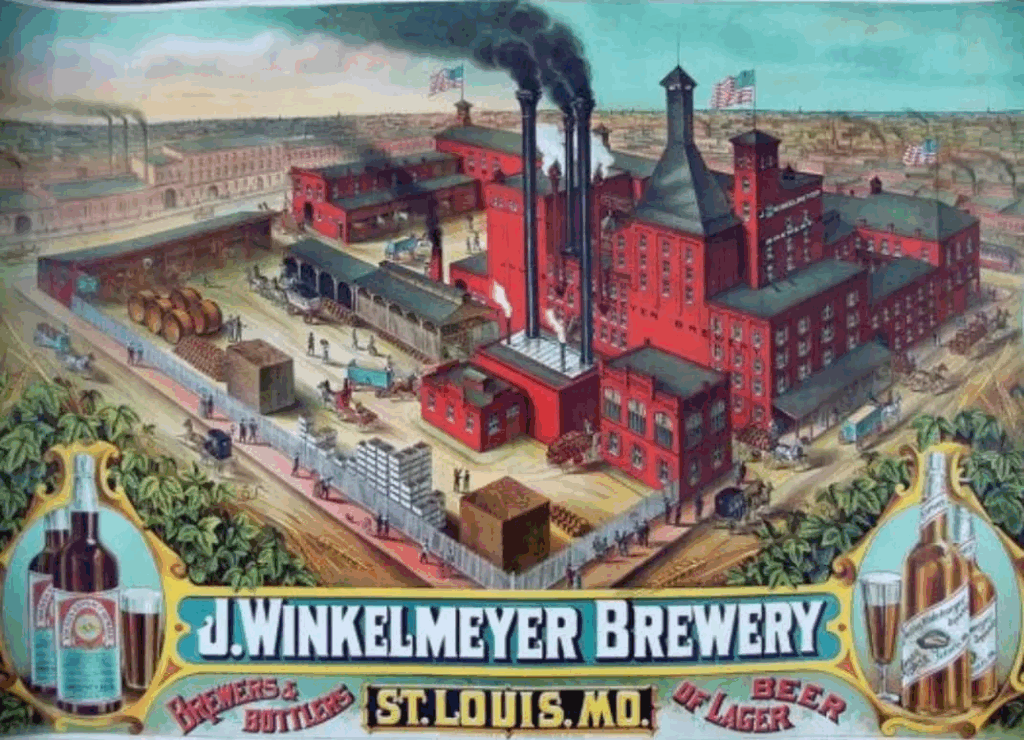

J Winkelmeyer Brewery postcard

Built on lager (and the caves beneath our feet)

Here, beer isn’t just a beverage — it’s part of the city’s DNA. In the mid-1800s, German lager traditions blossomed into a brewery in every neighborhood, with daily life orbiting beer halls and sprawling beer gardens. Our limestone caves made perfect natural cold storage for lagering (and enjoying the brews during the muggy St. Louis summers!), and the post–Civil War boom elevated names like Lemp, Winkelmeyer, and Griesedieck, as well as Anheuser-Busch, before Prohibition and consolidation thinned the ranks.

Today’s beer scene still winks at those roots. Breweries such as Urban Chestnut, Civil Life, and Schafly Brewing Co. celebrate German styles, and the comeback of beer gardens revives the sociable drinking culture that those immigrants introduced to the city.

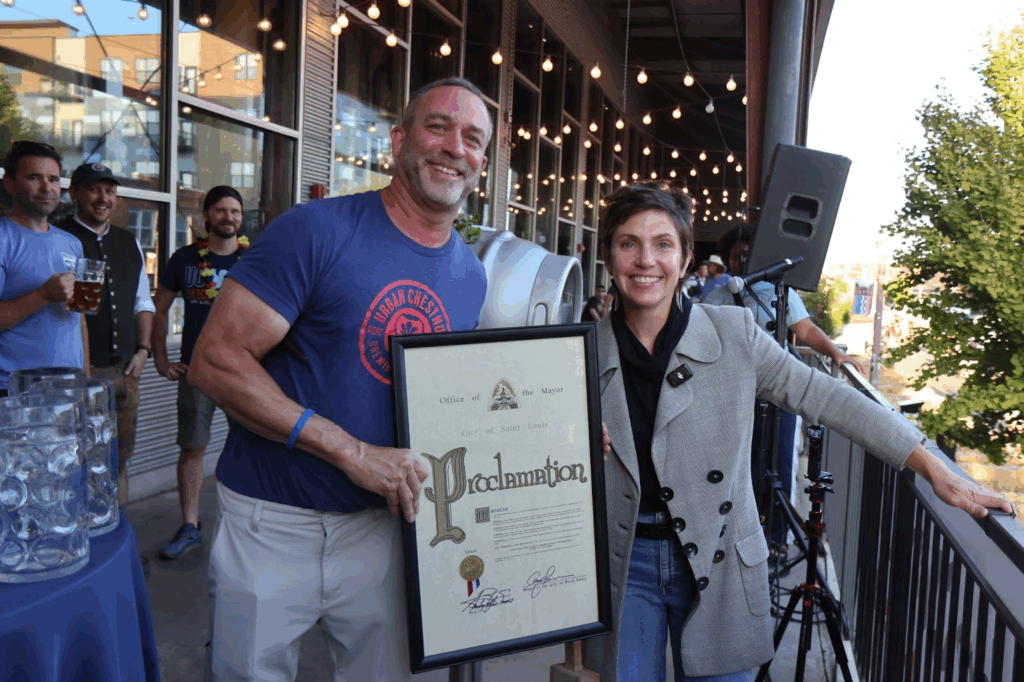

This year, Urban Chestnut hosted a large 3-day Oktoberfest in the Grove featuring their seasonal beers and live music. They welcomed the mayor of St. Louis, Cara Spencer, who presented them with a proclamation and successfully tapped the ceremonial first keg with a wooden mallet.

Urban Chestnut co-founder David Wolfe and St. Louis Mayor Cara Spencer with proclamation recognizing UC’s Oktoberfest 2025. Photo by Jackie Dana

David Wolfe ouring the first beer at Urban Chestnut after tapping the ceremonial keg. Photo by Jackie Dana

Still raising a stein: Oktoberfests in October

While some Oktoberfests have already happened (there are so many they start in September!), there are a few around the area you can still catch:

- Soulard Oktoberfest October 10th & 11th

- Oktoberfest at Westport Plaza October 17th & 18th

- Zootoberfest at the St. Louis Zoo, October 4th & 5th and 10th, 11th & 12th

- Oktoberfest in Hermann, MO, every weekend in October

Why it still matters in St. Louis today

If you know where to look, you can see the legacy of German immigrants everywhere— in our street names, the architecture of homes and office buildings, landmarks like Bevo Mill, our long tradition of local breweries, and in our festivals, including Oktoberfest.

In short, Oktoberfest in St. Louis isn’t just about steins and oompah; it’s a living thread that ties the region’s German roots to today’s neighborhoods. From 19th-century arrivals who helped build the city to modern-day festivals that carry their traditions forward, we continue to raise a glass to the people and places that have shaped St. Louis.

For more context and history, explore the sources below.

St. Louis German Americans | Nine PBS Special

St. Louis caves — and the breweries that loved them

German Cultural Society of St. Louis

A Preservation Plan for St. Louis, Part I: Historic Contexts