If you’re familiar with St. Louis brewing history, you are probably at least aware of the Lemp Brewery, whose most recognizable structure sits in the Marine Villa Neighborhood at Lemp Avenue and Cherokee Street. It is a hulking presence of brick, stone and iron that is a reminder of the beer barons that shaped St. Louis culture and business over the years.

But that brewery, parts of which are now crumbling into the sidewalks due to suburban

slumlord inactivity, was a product of William Lemp, son of Adam Lemp. Adam Lemp’s story is one shrouded in mysteries and contradictions that lends itself to curiosity for anyone interested in St. Louis history.

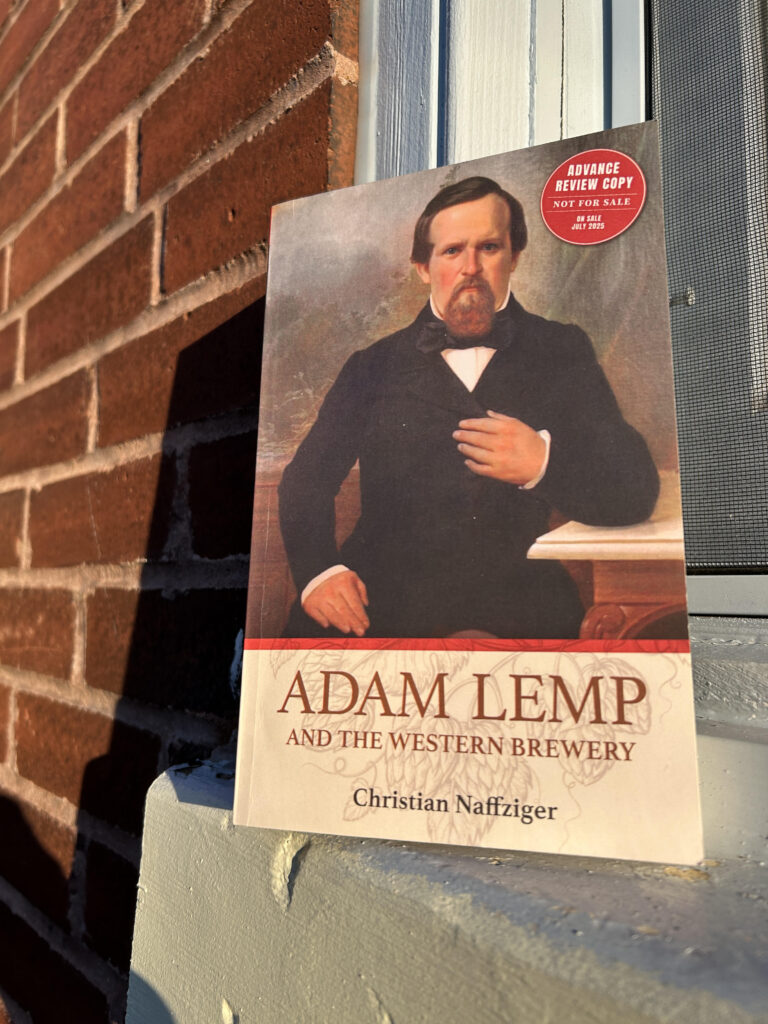

Enter St. Louis resident Chris Naffziger, a writer, historian and photographer. In addition to Naffziger’s documentation at St. Louis Patina, where he’s been “detailing the beauty of St. Louis architecture and the buildup of residue-or character-that accumulates over the course of time” since 2007, he has written several articles on William Lemp and the Lemp Brewery complex.

Naffziger’s latest book delves into the life and career of Adam Lemp, the father of William and the first German brewer to build the Lemp legacy in St. Louis. The book, “Adam Lemp and the Western Brewery” is meticulously researched, and includes some light commentary and perspective from the author, making it a great read.

What you get in this book is a cumulation of many hours over the course of several years, all done by a local writer who can take a walk to see these important sites anytime a modern point of reference is needed for inspiration.

I sat down with Chris to get his perspective and explore some questions I had after breezing through this part of St. Louis history in the 1800s.

Johann Adam Lemp was born in Germany somewhere between 1793 and 1798. There is even mystery surrounding his exact birth date. But German newspapers and other crucial documents are becoming digitized and available for researches the world over. Naffziger took advantage of these new resources to build the strongest document to date on Lemp’s life and times in St. Louis.

On Lemp’s birthday, Naffziger states: “the exact date of his birth is still problematic.” This admission and mystery from the author is repeated throughout the book where future research and documentation could reveal the true story, but Naffziger is forthcoming about the loose ends in his story, making this a fascinating read. Adam Lemp pretty much abandoned his first wife and children and immigrated to the United States in 1836 with his brewer’s yeast in hand, leaving a string of debt and bad early brewing decisions behind. He eventually reached St. Louis via Cincinnati where he settled down in what is now considered Downtown St. Louis. He started lagering beer and built up a property that included a cave and farm like setting complete with grape vines and livestock near the site of the current Lemp Brewery structure.

His accomplishments are undoubtedly important and impressive. The book allows the reader to consider William Lemp’s potential resentment of his father who left his mom and he behind, saddled with debt. How he eventually decided to support his dad and immigrate to the US to build a bigger and better brewery with the resentment and personal pain on the backburner. William ended up with half the brewery after Adam passed, so it all worked out financially in the end…but, the potential resentment is

obvious.

The book sheds light on Lemp’s business decisions, connections to the Civil War and German American’s role in abolitionist history. The book flows extremely well making it a good read, all the while providing copious and meticulous references and citations. This is a quintessential American immigrant story. The American dream, escapism, political activism, fortunes made, despair and mental ills…it’s all there.

What I liked most was Naffziger’s unanswered questions and positing about what he thinks as a prominent scholar on the Lemps. He also delves into some very interesting side characters in the book.

Per Naffziger, “Adam Lemp is the main line running through the book, but there are all these peripheral characters”. Naffziger does a great job of laying out the personalities and connections to Lemp.

Lemp benefited from some very loyal and talented employees. Naffziger describes some of these side hands in detail, their stories are fascinating as well, and previously unavailable to readers. Naffziger said, “he did in fact have a major part in the success of the brewery, but he also has some great lieutenants who kept it running.”

For instance, a common laborer named Christopher Huth was hired to clear land for a fruit and cattle farm on Lemp’s property. He was offered $5/day to clear the land, and all the beer he could drink. Naffziger said that this part of the city was in the middle of nowhere at the time. It was unimproved land with a farmhouse. The employees at the farm doubled as watchman for the cave entrance.

Then there was Louis Bach, one of Lemp’s shrewd business partners who had a pro- Union shooting club, which could be interpreted as an abolitionist militia). Lemp was part of the The Radicals Party who were more pro-Union and anti-slavery than the Republicans of the time. Germans helped seize St. Louis for the Union very early, and we owe them a lot.

It wasn’t even clear to Naffziger how well Lemp spoke English, the Lemps hired mainly German employees, initially Germans from Hessen, where he was originally from. It wasn’t even certain if he spoke fluent English, another mystery. Naffziger did learn that the Western Brewery on 2 nd Street was primarily a German neighborhood at the time. Naffziger details several petty, if not hilarious court indictments when the puritans and do -gooders were trying to bust him for selling beer on Sundays. He basically raised his middle finger in the air, fought the cases in the courts and carried on. Goodspeed to the rebels.

Naffziger thinks this pushback could have been performative anti-German sentiment from the English-American Protestant ruling class at the time. It reads like a tabloid and is quite juicy and hilarious to read.

Lemp could be cruel and kind at the same time. He was complicated. His good was evidenced by a family friend and business partner John Kaekell, who died by “sun stroke”. Lemp didn’t believe it and paid for an autopsy on the exhumed body. They wanted to vindicate him, but Naffziger assumes Kaekell was in financial troubles and committed suicide. Naffziger even contacted the National Weather Service to see how hot it was on that day. No records exist to help disprove the theory, but welcome to the mind of a historian and researcher. Naffziger supposes the weight of failure mixed with heavy drinking likely took Mr. Kaekell down. He also could have been ambushed by a debtor, this part of the city was the country back then and very remote.

Lemp was likely a bigamist and an alcoholic (he died of cirrhosis of the liver), if not a bit bipolar or a touch ADHD. I asked Naffziger, what Lemp’s modern diagnosis would be? He said the curiosity of opening multiple breweries in Germany, branching off to a winery in St. Louis and the farm pastures near the Mississippi River, all point toward ADHD and lack of focus. However, Lemp leaned on his friends like Louis Bach who had the business acumen to steer the Lemp ship toward the light.

I was curious if Lemp would have been considered rich or a societal elite in the 19 th century. Naffziger said he was never a millionaire, but he did well for himself. He firmly established himself in the upper middle class, if not the upper class of St. Louis. A skilled laborer back then made $1/day. So making $40,000 a year was a big deal. Naffziger documented paystubs for quarry men and carpenters. Federal census data documented that his brewery workers were making $1/day. He was doing so well that around 1865, he built the Adam Lemp villa (razed in the 1940s), 100 feet north of

eMenil Place and Cherokee Street.

Lemp was likely not in the same league as the Anheuser’s or Chouteau’s of the time but was definitely making significant money and commanding respect.

What sets this book apart is Naffziger’s curiosity and admissions of unsolved mysteries. When he says he’s still confused on a particular subject, you believe him. But he lays out his theories, and isn’t that what’s fun about historical nonfiction?

Naffziger summed up his writing style as “scholarly research written for regular people.” He included copious citations since, in some cases, these are published firsts due to the availability of these newly digitized resources. So, if you do want to take an academic approach to reading the book, or digging deeper into your own research, the facts and connections are all there.

There have been other books written about the Lemp family, and Naffziger’s friendship and connections to past writers like Steven Walker’s make his book a perfect companion to existing texts. The vast majority of Walker’s “Lemp: the Haunting History” from the late 1980s had limited investigation into Adam Lemp, focusing primarily on William Lemp. Another key paper, written by M.A. Lindhurst, a Washington University graduate student, in a Master’s Thesis from the 1930s. While it is well written and interesting, Naffziger found inaccuracies that were corrected as more information is available, found and recorded. It helps that Naffziger can speak and read German and much of his findings were from German language newspapers published in Germany and St. Louis.

I asked why a book, and not an online paper? Naffziger originally envisioned his research as an article submitted to the brewing history journal in England. But when the research was completed, there was so much more to the story and that’s when Naffziger decided on a book, and Adam Lemp in particular had not been documented to this level.

His most helpful resources included German language newspapers, the Missouri Historical Society and the Recorder of Deeds office in St. Louis. The latter was essential for understanding the caves used for entertainment and lagering dating back to 1841, previous research said he started using the cave in 1846. Ah, the truth is much more clear.

And this could be important for those trying to identify who the first American’s were to lager beer. Was it the Yuengling folks in Pennsylvania or the Lemp’s right here in St. Louis? The book proves lagering in St. Louis was documented earlier than previously thought.

Other interesting curiosities that tie current uses to those from the past, Naffziger described two Lemp Parks, the first was a beer garden near DeMenil, Cherokee, Lemp and Utah Avenue. And the now Cherokee Park in Benton Park, was William Lemp’s vaudevillian amusement park. The former was sold by Adam to raise money for the brewery and his son, William.

The man-made 100-yard cavern beer garden was built by William and is under the current Cherokee Street.

The book concludes with a fascinating story about the final resting places of Adam Lemp with the rest of the family that gives you insight into the family dynamics and relationship between William Lemp and his parents.

“Adam Lemp and the Western Brewery” is a great read with little filler that doesn’t serve the story. It is entertaining and isn’t bogged down by minutia present in many a non- fictional account of centuries past.

This makes Naffziger’s first book an essential sibling to the previous published bodies of work. Pick up a copy at your favorite bookstore or library July 9th , 2025.