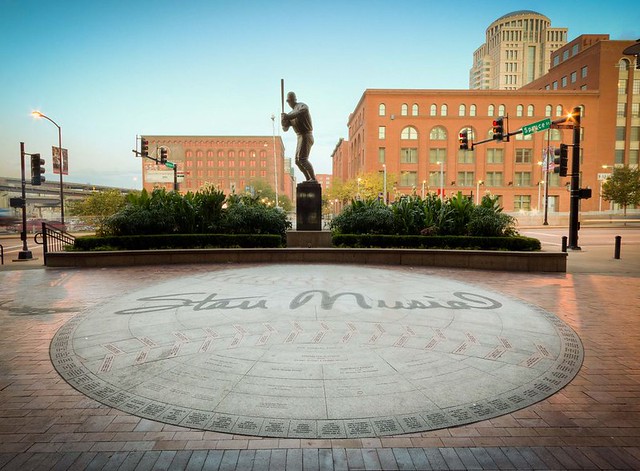

{Stan stands poised to send a liner straight up Spruce Street – image by Ben Evans}

Stan Musial, baseball’s perfect knight, died yesterday evening. When I found out—via text message from a friend—I was not exactly sure how I felt or how I should feel. Mr. Musial’s death could not be called unexpected. He was 92 years old, and his declining health had not gone without notice. He did not leave any unfinished business or old grudges, as far as I know. It is the kind of death about which people can remark “Well, he lived a good life.” While this is true, it is also patently insufficient. Musial was a man who had taken on mythical status in the city of St. Louis. In a city that worships baseball, he was a god who walked the Earth, and he was revered accordingly. Any time he would show up at a game or other public appearance, there was a feeling of magic in the air. I never met Stan Musial. I will never meet Stan Musial. That fact makes me surprisingly sad.

I called my mom last night. I wasn’t sure what else to do. Because I was calling much later than I normally do, she answered the phone sounding worried. Stan Musial died, I told her. After a sad sigh, she responded: “Isn’t that strange? I was just thinking about him this afternoon.” Me too, mom. I was thinking about him that afternoon too.

I have noticed several narratives around Musial that will likely reemerge as we celebrate his life and career. First, especially within the city, I expect to see the righteous indignation of those who (rightfully) believe that Stan has never gotten his real due. They will point to his career statistics and remarkable consistency, his respect for the game, and his iconic stance and swing. They will question his inexplicable absence from national conversations about the greatest baseball players.

It might be because of where he played: outside the media spotlight and self-infatuation of the biggest cities. It might be because of how he played: excellently, but not in a flashy or especially eye-catching way. It might be because of when he played, in an era marked by players (including Stan) trading prime playing years for military service, and overshadowed by other all-time greats. It might be because of what he did when he wasn’t playing: nothing that would be deemed exciting or scandalous enough for media coverage. For whatever reason, Stan Musial will almost certainly not get the recognition he deserves as a player.

One could take a more nostalgic perspective, holding up Musial the man as an icon of a lost era. He will, not incorrectly, be described as a champion of hard work and hard play that stands out all the more starkly in an era in which players will do whatever it takes to gain an advantage and make a bigger paycheck. The title of the New York Times’ article on his death: “Stan Musial: Substance Over Sizzle.” He smiled, played the harmonica, and generally endeared himself to all who came into contact with him. He attended mass regularly. He was married to the same woman for over 70 years. While athletes today seem increasingly comfortable playing the role of overgrown child or anti-hero, he accepted the responsibility that come with being a role model. He is the kind of figure that makes it easy to romanticize the past.

I myself often use Musial as a symbol of what I love about St. Louis. Musial was an embodiment of the vague mystique that is “Cardinals baseball”, something that involves playing the game “the right way” but is so much more than that in a way that’s tough to say. He played a hard nine. He was understated excellence. After his playing career was over he stayed here. Our little secret. The lack of recognition—and his indifference to it—only made him more special. It didn’t matter that others didn’t get it. We knew, after all.

These narratives have value. None of them are incorrect. All of them are limited. So what does his death mean, at least for me? I am far too young to have seen Musial in action. Musial the Player exists for me as grainy newsreel clips, firsthand accounts, and pages of statistics. I was raised on Musial the Legend. I remember my dad excitedly telling me about running into Stan while getting lunch at Beffa’s. I have shared the stories passed down by those who played with and against him, by those who umpired or announced his games. However, in retelling the Legend of Musial it is all too easy to forget that he was a man, a human being. He was a man lucky enough to play a sport he loved and to do so extremely well. He knew how lucky he was. The word that most comes to mind when I think of him is decency. It is a word that does not lend itself to extremes, and often has connotations of mediocrity. His life defies those definitions. He was exceedingly decent. That in itself is beautiful. It needs no greater narrative or additional context.

Mr. Musial, thank you. We are lucky to have had you. I’m going to miss you. I’m really going to miss you. We all are.

*Editor's note: the headline is a reference to the mention of Joe DiMaggio in the Simon & Garfunkel song "Mrs. Robinson". From Wikipedia: In a New York Times op-ed in March 1999, shortly after DiMaggio's death, Simon discussed (a meeting with DiMaggio) and explained that the line was meant as a sincere tribute to DiMaggio's unpretentious heroic stature, in a time when popular culture magnifies and distorts how we perceive our heroes. He further reflected: "In these days of Presidential transgressions and apologies and prime-time interviews about private sexual matters, we grieve for Joe DiMaggio and mourn the loss of his grace and dignity, his fierce sense of privacy, his fidelity to the memory of his wife and the power of his silence." Seems fitting. – Alex